A repository for this article can be found here.

When most developers think about request tracing, they picture instrumentation hooks inside familiar libraries. This allows us to track familiar metrics we see in application performance monitoring (APM) tools such as the duration of an HTTP call or how long a database query takes. But what if you could go deeper and instrument your own Ruby code automatically, without sprinkling timing calls everywhere? This is what we call AutoInstruments and where the Ruby Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) and the Ruby parser (Prism) come into play.

We’ll skip the long and fragmented history of Ruby’s parsers and interpreters and just note that for our purposes, as of Ruby 3.4, Prism is now the default Ruby parser (introduced as a default gem in Ruby 3.3) and is responsible for turning Ruby source code into an AST. From there, the YARV virtual machine, Ruby’s bytecode interpreter since 1.9, compiles and executes it.

Let’s peel back the various layers of instrumenting code automatically and see how it works in practice.

Understanding YARV Instruction Sequence

Since we need to transform and modify Ruby source code, it helps to first understand how YARV takes that source, compiles it into bytecode, and executes it. Ruby exposes this process through the RubyVM::InstructionSequence class, which lets us compile Ruby source code into its underlying instruction sequence.

In this we can either compile a file using compile_file_prism or raw source. For this example, we will just use raw source:

3.4.2 :002 > insns = RubyVM::InstructionSequence.compile_prism("puts 'HI WORLD'")

=> <RubyVM::InstructionSequence:<compiled>@<compiled>:1>

When we do this, we get an instruction sequence which allows us to do a few things. One of which is that we can disassemble it to show us the produced instructions in human readable form:

3.4.2 :003 > pp insns.disassemble

"== disasm: #<ISeq:<compiled>@<compiled>:1 (1,0)-(1,15)>\n" +

"0000 putself ( 1)[Li]\n" +

"0001 putchilledstring \"HI WORLD\"\n" +

"0003 opt_send_without_block <calldata!mid:puts, argc:1, FCALL|ARGS_SIMPLE>\n" +

"0005 leave\n"

Another is to tell it to evaluate the instructions as well:

3.4.2 :004 > insns.eval

HI WORLD

=> nil

For a more detailed look into YARV and these various instructions, see Kevin Newton’s (the creator of Prism) series the Advent of YARV.

Also Ruby Under a Microscope is getting a 3.x edition, so check that out as well.

Load_iseq Hook

With the ultimate goal of dynamically adding instrumentation to a source file, we need a way to intercept when a file’s instruction sequence is loaded — for example, during require 'path/to/file.rb'. The idea is to modify the source to include our instrumentation before returning the instruction sequence for the altered code. That’s where load_iseq comes in. By prepending to this method, we can intercept the normal instruction sequence, use Prism to parse the file into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) — the same structure YARV builds internally — perform the necessary transformations, and then return the modified instruction sequence.

module Patch

module InstructionSequence

def load_iseq(path)

# Return the path/file’s altered source’s instruction sequence

self.comile_file_prism(transform_file_source(path))

# What normally occurs:

# self.compile_file_prism(path)

end

end

class << RubyVM::InstructionSequence

prepend InstructionSequence

end

end

For example, if we look at Part 1, in the example.rb we are running:

puts “HELLO WORLD”

However, in the patch.rb, we are saying to instead use ‘puts “HI WORLD”’.

When we run the example file along with the patch (note the order):

ruby -r ./patch.rb -r ./example.rb -e 'exit'

We see that we get HI WORLD even though example.rb had puts HELLO WORLD in it.

Let’s take this a step forward and discuss how we can create the transform_file_source part of the equation.

Swapping method names using the AST

Many links below will point to docs found in the Advent of Prism by Kevin Newton.

There are many things that we can do to transform the source of a file. While adding our instrumentation to the source automatically is our goal, let’s start with a simpler application. What if we want to swap the names of a method? There are considerably easier ways to do this in Ruby, such as alias_method, but let’s see how we can do this with the AST/Prism parsing and swapping out some of the Ruby source code for compilation. For this example, let’s try and swap the method name in part 2’s example.rb, so that if we run it the greet call will work as expected.

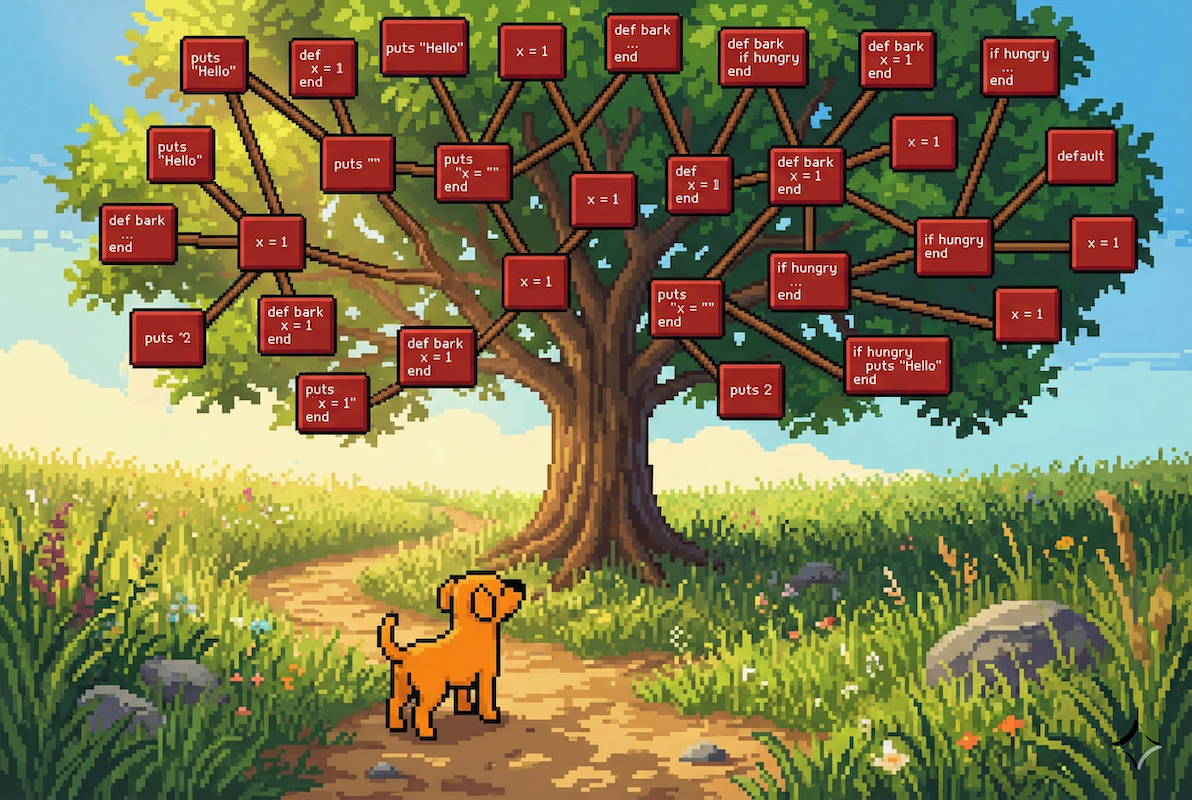

At the same time when looking at part 2’s example.rb we can see a simplified AST (in part 4 we will write out the AST for each required file) that we get when we parse it with Prism. At the top we find that the root most node of the AST for Prism / ParseResult is going to be ProgramNode followed by a child node of StatementsNode. With the AST being a unidirectional tree, if we are wanting to swap the names of a method (such as greeting to greet in example.rb) we will need to recursively check the child nodes from ProgramNode -> StatementsNode, down until we find a DefNode with the old name of greeting. Once we find this DefNode, we can get the Location of where the node is in the source. Once we have this bit of information, we can then overwrite this source location with the new method name.

One thing of note, is that since the Location gives offsets in bytes, we will need to set the encoding of the source string to ASCII-8BIT (utilizing String#b), otherwise we may run into issues where non UTF-8 characters, such as those found in comments (and potentially string literals), will cause index out of range issues when trying to replace the source. While YARV works with this encoding, in real world practice, we will need to convert these back to the original encoding, as we can run into situations of incompatible string encodings.

As seen earlier when looking at part 2’s example.rb, since there is no method defined of greet but instead greeting, if we run it:

ruby -r ./example.rb -e 'exit'

We will get a undefined local variable or method 'greet', but if we require the patch first (which redefines greeting to greet), we see:

ruby -r ./patch.rb -r ./example.rb -e 'exit'

Hello World

Instrumenting Method Calls

Now that we’ve covered the general high level structure of the Prism AST, let’s take a look at how we can go about instrumenting method calls. In a nutshell our instrumentation is really just a simple timing:

start_time = Time.now

# do work

end_time = Time.now

puts "Work took #{end_time - start_time}"

Given this, we can tweak this a bit to be more reusable with something as simple as:

class Timer

def self.capture

start_time = Time.now

yield

end_time = Time.now

puts "Capture took #{end_time - start_time}"

end

end

Timer.capture do

# do work

end

Building on this foundation, we can build up to something that resembles a span/layer with timings, which would match the API that we have here at Scout:

ScoutApm::Tracer.instrument("Category", "Subcategory") do

# do work

end

So to properly trace we really just want to inject our timing API into the source code wrapping any method calling.

def some_work

# do work

end

ScoutApm::Tracer.instrument("Work", "some_work") do

some_work

end

That’s really the crux of it. However, just like many things in life, the devil is in the details. In Ruby, there are many many ways that calls can be made in Ruby.

Class Method Wrapping

For the vast majority of Ruby code written, it is likely written where the file contains a single module or class which may contain child modules and classes with their respective methods. This is especially true for controllers in Rails, which is what is parsed with the AutoInstruments feature.

It’s at this point where we start to see the complexities of the AST start to build. As such, we should really be writing out the AST of the file that we are parsing, as well as the rewritten version of it to verify that we are indeed creating the correct source, with our intended instrumentation wrappings.

In fact, we start to see some of this right as we go and try and instrument a something like:

Testclass.new.greet

If we use the patch.rb from the previous section we end up with something like:

BlockCaller.yielder('new') { TestClass.new("Hello, world") }{ TestClass.new("Hello, world").greet }

I don’t think that’s what we want. In fact, what do we want? Do we want a wrapper around greet or new or both? If we look at the part 4 example_ast.txt, we see that .new is a receiver / child node of .greet. As such, we may want to not to instrument nodes whose parent nodes are currently being instrumented. How can we do that? With Prism being a unidirection tree, each node won’t store references to its parents. As such, we need to manually keep track of these relationships either via a hashmap or something like a stack.

For this case, we are going to use a stack as we just need to know about the current node’s parent(s), and whether the parents were a CallNode. Once we are done processing the node, and if it is a CallNode, we will pop it off the stack to ensure sibling CallNodes do get instrumented if one of their ancestors wasn’t a CallNode. Once we have done this, we end up with the correct instrumentation as follows:

BlockCaller.yielder('greet') { TestClass.new("Hello, world").greet }

When it comes to parsing the AST and injecting / rewriting the source, a lot of it is handling various cases on how particular methods can be called, and the various ways that these nodes & method calls are related to one another.

This is the foundation of how Scout's https://scoutapm.com/docs/ruby/features#auto-instruments feature works under the hood, leveraging Prism and the AST to automatically trace your custom Ruby code without requiring any manual instrumentation. The result is deep, method-level visibility into your application's performance, right out of the box. Ready to see what's happening inside your Ruby app? https://scoutapm.com/users/sign_up and start tracing in minutes.